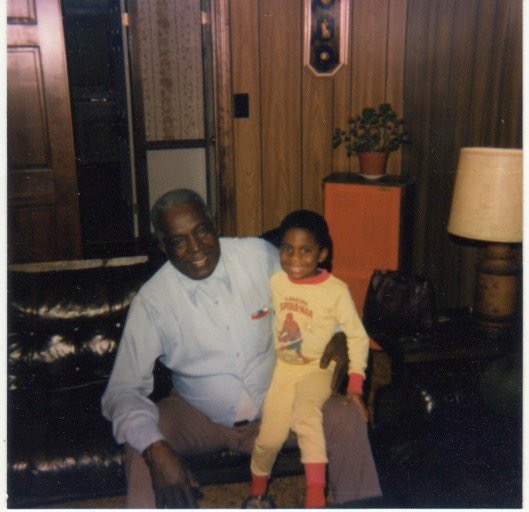

Peter Joseph Smith (1913 - 1984)

I awoke one cold grey morning in the fall of 1984 to the news that my Granddaddy, Peter Joe Smith, had passed away. He was 70 years old, and had been struggling for a long while with emphysema. I was 9.

I remember the creak of the door and the unwelcome light pouring in from the hallway. My mother entered my bedroom with a heaviness in her eyes that I rarely saw. I could feel the temperature change. "Granddaddy died last night," her voice trembled. I felt a pang of grief at the bottom of my belly as I tried to process the words.

Peter Joe was the first older person who ever made me feel like I had a friend. I always felt loved by my parents and siblings, but Granddaddy was my buddy. I always looked forward to my time with him. I'd walk into my grandparents' home, through the wood-paneled corridor between the front door and the living room, and I would hurriedly make my way to the kitchen where I would see him hunched over the table. He was a dark skinned man of medium build, with square shoulders and large leathery hands. His were the hands of a man who built his own home, brick by brick. His eyes would grow wide and he would flash a bright, dimpled smile. "Hey, Mister Man!" he would exclaim with as much breath as he could muster. He was always so happy to see me. With him I would spend hours; I would sit rapt, eyes wide, as he spun stories about his childhood.

Grandaddy's funeral is the first one I vividly remember. I can still see the colors; burgundy velour on the church pews, stark white walls, Reverend Scott's black robe adorned by a long red shawl. I can hear the drone of dark chords on an organ and the horrible sounds of wailing. It was my first account of true and inconsolable suffering; the first time I became aware of how small I am -- how infinitesimally small we all are -- within the larger continuum of time. All of these big strong people, men and women that I'd known for all of my short life, were suffering a deep and seemingly bottomless sadness against which we were all defenseless. We're so sad that he's gone, I remember thinking, we must have loved him so much.

As we made our way out of the church, Daddy and me approached Granddaddy's open casket. "Daddy, I don't want to look," I whispered. Dad draped his arm over my shoulder. "Just turn away, son." I did.

At the graveside my grandmother Mildred, Peter Joe's wife of nearly fifty-one years, sobbed and shook as his casket sank slowly into the ground. Cold wind blew angrily. The sun hid behind a passing cloud.

About seven years ago, I found a crumpled picture of Peter Joe at the bottom of a drawer in my old bedroom. I became enamored with it, as it so perfectly captures my memories of him. My brother generously took the time to enhance, enlarge and print it and had the photo framed for me as a gift for my 35th birthday. It hangs on a large wall in my New York apartment. It is my single most cherished material possession.

Now, when I turn the key to this place, which is so far removed from the place and time in which I knew him, I get to see him every day. He's still standing right there as I remember him, on the front porch of his home with the sunlight cascading over him. He's wearing his yellow shirt, his striped tie, his brown slacks, his face aglow with a bright, dimpled smile. He's still happy to see me.